TW: Suicide

This year’s Fall Reading Break has ended much like any other: I’m trying to recuperate my energy to keep going for another six weeks under the crunch of the austerity regime at my workplace—taking longer walks, cooking more elaborate meals, and doomscrolling a little less.

But this year feels different. I find myself reflecting on the years of work, organizing, and consultation it took to establish the reading break in the first place. When it was finalized and became official, beginning with the 2022-23 academic year, only a handful of people remembered how the discussion started and how urgent the need for a fall reading break was. I was reminded of that process recently by a short piece from the Journal reporting on massive TA cuts in first-year courses. It was a painful flashback for me.

The requests for a fall reading break from students started in 2007. The campaign gained momentum after Queen’s made headlines (yet again!) in 2011 when multiple students lost their lives on campus, many to suicide. It was truly a gut-wrenching time for everyone on campus. In response, then-Principal Daniel Wolfe established the Commission on Mental Health, which released its report in November 2012 with over 100 recommendations, including the implementation of a fall reading break. At the time and in the years following, there were many criticisms towards the mental health (later “wellness”) framework that emerged from this process for lack of resources, for not acknowledging social determinants such as sexism and racism, and for its over-medicalized approach. Beneath all those critiques, however, ran one silent constant: austerity.

Because in the background of the discussions of mental health on campus between 2010-2015, and in the midst of tragedies of student loss and a genuine mental health crisis, another round of (soul) crushing austerity was reshaping the university.

Eternal Return of the Same

In 2010, Principal Daniel Wolfe released his vision document titled “Where Next?” Spoiler alert: What was next was Principal Wolfe’s second vision document (The Third Juncture) and later the most recent Bicentennial Vision document by Principal Deane. Read together, they resemble a recycled student paper.

Where Next? unleashed the post-2008 financial crisis austerity on campus, of which Wolfe said:

“Like many of our peers, Queen’s is facing fundamental choices. Economic, social and technological revolutions are underway across the globe. We must be alive to this context – and our current financial situation – in our planning and decision-making. We must balance the budget over the next few years and to do so we must become more efficient. We will be undertaking a major governance review and the Vice-Principal (Academic) position will also become that of Provost in May; we are developing a proposal for a University Planning Committee that, if adopted, will bring together members of the Board of Trustees and Senate to ensure that academic and financial planning are better integrated and proceed in parallel. On the administrative side, we are implementing recommendations of the Cost-Reduction Task Force and we are considering bringing in external experts to help us identify any internal inefficiencies that may be costing us money.”

The 2010 round of austerity was particularly consequential. It marked the first major surge in undergraduate admissions, coupled with a hiring freeze. The result was a rapid spike in the student–faculty ratio. One interesting example was the School of Computing, then as now treated as a revenue-generating unit with minimal investment: its student-to-faculty ratio increased from 11:1 in 2011 to 19.5:1 in 2014.

Admissions grew so quickly, and with so little consultation, that there weren’t enough physical classrooms for large courses. Online teaching was introduced as a “two-birds-one-stone” solution: more students, less need for space, more revenue. Arts and Science Online was the child of that initiative, only to be gutted a decade later under the current austerity cycle.

As they are today, collegial governance structures were under attack and departments and programs were on the chopping block. And just like today, anti-austerity faculty, staff, and students were challenging the university’s creative budgeting, pushing for truly democratic collegial governance, and questioning the early signs of higher administration bloat in the middle of a hiring freeze.

In short, there were more students on campus than ever before, and services were under a heavy budget burden trying to stay afloat. International students were dropped on campus with minimal resources available to them and treated primarily as a ‘revenue-generating unit’. Faculty and staff were organizing, yes, but working under immense stress. And students, particularly first-year students, bore the brunt of this manufactured chaos. I argue that the effects of the university’s austerity policy were the true drivers of the 2010 mental health crisis.

The university’s position, on the other hand, was not short of moral bullying: forcing everyone to choose between complying with cuts or supporting mental health. As former rector Mike Young was stating in 2014:

“Our options this year were to increase enrolment and maintain our budget, or sustain enrolment and have a reduced budget for student services. So either have more students need help and maintain your funding, or maintain the number of students and reduce your funding. So it’s a lose-lose situation”.

Another spoiler alert: it was both: increased class sizes and diminished central services. It was always a false choice. The university adopted the corporate model in addressing the mental health crisis, relying heavily on individualized solutions, understanding “resources” as anything but human resources, and actively omitting the impacts of its austerity regime.

The faculty called it out. For instance, Elaine Power told the Journal in 2014:

“Despite all the attention paid to individualized mental health remedies on campus, I worry that university initiatives — such as increased enrollment and altered class formats — don’t account for the mental health implications of students being treated primarily as revenue sources.”.

Beverly Mullings pointed out the toll on staff and faculty under the austerity regime:

“Faculty now must work longer, compete harder to bring research grants into the university and, increasingly, find new ways to generate revenue. As opportunities for full-time and protected employment become more precarious, questions of mental distress among academic faculty and administrative staff will continue to remain largely taboo and invisible.”

Indeed, faculty numbers were dropping beyond “normal attrition.” Teaching faculty fell from 815 in 2009 to 768 in 2013.

Quiet Quitting is Over, Welcome Quiet Cracking

During the pandemic, which opened the floodgates for the further normalization of overwork and the erosion of work-life balance, a new term emerged: quiet quitting. At the time, business magazines and journals were warning employers that the passion for work was disappearing and the majority of workers were prioritizing their wellbeing and values over their jobs (so a work-to-rule, as to those who are familiar with labour rights). Since then, there were probably thousands of posts on corporate networks, especially among people working above middle management, on how to prevent quiet quitting in the workplace. The wannabe-corporate-university sector responded to it by “personalized” events to create meaning in the workplace. (Has anyone recovered from the 2021 Zoom Christmas Parties?). In a sense, what was offered as a solution to the 2010 mental health crisis was now extended with a rush to staff and faculty so that no one quiet quits from “doing more with less”.

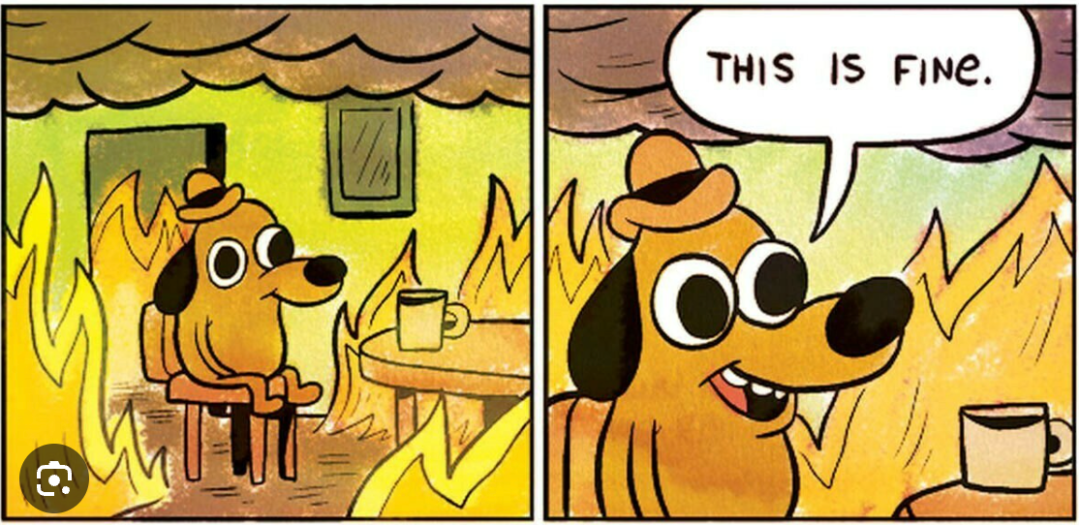

Now, we are at another turning point, and LinkedIn’s middle management circles are on fire again. In August 2025, Forbes magazine warned employers about another trend emerging among the workforce as a “response to workplace financial trauma”. (note to self: austerity has been rebranded as financial trauma). This, according to Business Insider, can be called quiet cracking: “the silent struggle of feeling dissatisfied at work and unable to leave”. Fortune magazine reports that half of the American workforce is experiencing “symptoms”: “The telltale signs of quiet cracking are very similar to burnout. You may notice yourself lacking motivation and enthusiasm for your work, and you may be feeling useless, or even angry and irritable”.

Are you cracking yet?

If you survived the last section, good job! This corporate double-talk, this shiny new language for old stories, does not change the underlying truth. Austerity (‘financial trauma’ for the Board of Trustees) creates an unbearable workplace. Not only through overwork, but through the constant anxiety, depression, precarity, and erosion of motivation it produces. Its toxicity seeps into personal and collegial relations, corroding the soul of the workers.

Of course, this is not new to the higher administration either. They knew about the crisis in 2010, and they know about it today. In fact, the most recent Queen’s Employee Experience Survey results identify “employee recognition, support and resources for mental health, and opportunities for professional development” as targeted improvements. So the question isn’t whether they know — it’s how they respond.

In their dissertation on 2010-2015 ‘mental health crisis response’ at Queen’s, Andrea Phillipson looks into the nexus of corporatization of higher education and mental health response. They conclude:

“Acknowledgement of distress in the academy is integral to its process of corporatization because this acknowledgement prompts the emergence of the caring community that is directed back to corporate-like and corporate-linked solutions to this distress.”

In fact, in the summer of 2024, amid the staff layoffs in FAS, we witnessed corporate-model wellness trainings being run consecutively with the layoffs. QCAA had a brilliant blog post reflecting on it. The aforementioned employee experience survey also mentions the new initiative “Enhancing Wellbeing and Preventing Burnout Certificate” as a response. Similarly,this year’s ‘Thrive Week’ focuses again on “corporate-like and corporate-linked” trainings and workshops such as “how to foster a grief-literate work culture” and workload management “in a healthier, more sustainable way.”

Would it be fair to say these workshops and “digital hygiene” reminders are failing miserably? Aren’t they bound to fail?

So, reader — how are you feeling?

How do you feel when you have an innovative teaching idea but know too well that your department head will say, “but the budget”?

When you juggle between dramatically reduced TA hours and maintaining the integrity of your syllabus?

When tasks suddenly land on your desk because the staff member who handled them for decades is gone?

When you hesitate to email a colleague because you know they’re at their breaking point?

Are you still excited about your research? About your teaching? Where is that spark that brought you into this work?

How many times have you checked job postings — anywhere but here — in the last five weeks?

Do you feel like you’ll snap the next time you hear “hiring freeze,” “structural deficit,” or “capital budget”?

Are these “fixable” by a corporate workshop?

What is actually cracking?

It’s not the workers who are cracking but the (re)structures around us.

Austerity, as in the 2010 cycle, is once again eroding the foundations of our work, shattering morale and exhausting our capacities; its impacts on students are already visible. This is why it is so painful when I hear about “reduced tutorial hours.” We have been there. It didn’t end well.

Last time, the administration’s “solution” was to send people home or to counsellors’ offices, whose numbers were only slightly increased, or to corporate “talk” programs. After all, the university never does the talking.

This time, though, we are all stuck in this cracking structure around us, crunched under the never-ending memos and townhalls. Will this town hall convince you that there is no other choice but to adapt? Can you please be more resilient while we quickly reshuffle your workplace? Take a walk, maybe, during lunch, if you could spare the time? You can’t?!

I am respectfully informing the higher administration, blowing the whistle, ringing the bell, raising the alarm, whatever you want to call it. I know you are reading this; you always do. The articles from your business magazines are telling a partial truth. Quiet cracking is not a new trend that shall pass. You have, yet again, a mental health crisis brewing. Cracking will not be quiet. It never is.

Ayca Tomac, PhD, is an assistant professor and continuing adjunct in Global Development Studies and Cultural Studies.

What an amazing and jarring post. This is exactly how I’m feeling. I used to be able to enjoy my weekends and get other things in my life done. Now I have to spend one entire day just physically and mentally recovering from the exhausting week I’ve had. But sometimes I cannot afford to do that because of the marking I have to get on top of with the TA cuts and I feel myself getting more and more depleted. I used to go to the gym but can never find the time now. I’m taking short cuts in other areas of my life and not able to make headway on my research during term time. I just want it to end.

LikeLike